II

"To understand recursion, you must understand recursion."

-David Hunter, Essentials of Discrete Mathematics, Jones and Bartlett, 2009.

The Aperture Record is a uniquely bound series of inter-medium recordings, all relating back to the timeline of events surrounding Aperture Science and its eventual downfall.[footnote] Many first-time explorers of the collection falter at the start, unsure what exactly the "start" even is. "Where do I begin?" is the most frequently asked question across Aperture Record forums, academic groups, university courses, journal articles, and informative leaflets - and every time it is asked, it receives a slightly different answer.

On the surface level, it is an inherently nonlinear narrative. The tapes were discovered in random order, the written documents spanning wildly different dates of time - if the dates are even to be believed. No matter where you start, you're starting in medias res, so to speak. A similar tune to James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake, it can be dissected from any angle - top-down, from the side, corner to corner, it all unfolds in unique and informative ways each time.

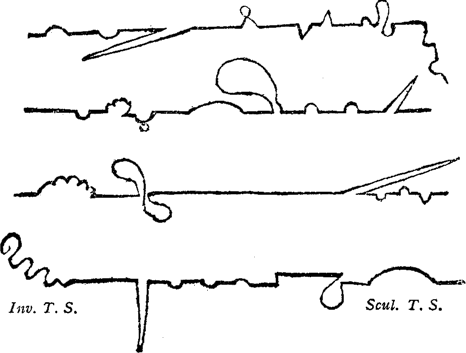

Consider, as well, Laurence Sterne's creation of a nonlinear narrative in The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Here we find a story that interrupts itself at every turn. The narrator, titular Tristram Shandy, goes so far as to illustrate the narrative himself, pointing out the various bumps, twists, turns, squiggles, and sharp zigs or zags that veer the story away from linearity and into abstraction.

While this is an apt visual description of the narrative, it still doesn't quite fit the extent to which the Aperture Record lacks linearity. In the end, it is still a man traveling forwards through time and telling a story beginning to end, no matter how many distractions, asides, allusions, metaphors, and in-jokes derail that story. In order to fully encompass the lack of direction here, the line should be twisted and joined at either end, loops of itself intersecting each other and forming a Möbius strip of narrative that infinitely spirals back into itself, expanding and contracting on a whim, no distinct start or end, only an ever-shifting narrative.

Perhaps, it would look something like this:

The iconic Aperture logo, small and inoffensive but emblazoned on so many inventions, chamber walls, menial forms, subject files and even stuck in the bottom corner of every second of security camera footage, it becomes impossible to avoid. It is a peculiar logo, all things considered - for a company founded on shower curtains,4 the iconography of a camera lens seems obtuse at best and intentionally misleading at worst. Yet, from a narrative sense, it performs its duty beautifully. Human pattern recognition has long since rooted in our minds inherent attributes to everything we see, even down to the simplest shapes. Triangles are sharp, dangerous, unstable. All straight lines and points, no soft curves to be found, the image of a knife's edge is immediately evoked. Yet the triangles of this logo intersect to form a circle, the image of comfort and calm. Welcoming curves that convey only safety, containment, comfort. Only when fully encircled in the embrace of those welcoming curves can one finally look around and see the sharp angles on the inside. Then, and only then, the aperture shuts.

The Aperture Record, of course, was content to remain nonlinear or even antilinear for the rest of time. It was us humans with our inherent desire to dissect, sort, and organize that changed that. While some are content within the abstract, and argue that subscribing any sort of order and sense to the Aperture Record inherently denies it its purpose, others have come together with overall favorable delineations of the materials.

Common consensus divides into two distinct schools of thought, known as such: The Intellectual Analysis, and The Emotional Analysis.(footnote)

Majority scholars fall into the former category, as is to be expected, while film students, artists, and coffee-shop analysts tend to favor the latter. There are, of course, different advantages and drawbacks to either choice, and many are of the opinion that in order to truly understand the Aperture Record, one must actually approach it twice - first for the feeling, second for the timeline. While this idea certainly holds much water, and revisiting the source material regularly is always a good idea, it is of this author's personal opinion that there is a glaring issue with both of these analyses as a whole.

That being, there is a linear narrative in the Aperture Record.(footnote)

It is hard to detect. In fact, many academic papers and analyses fail to catch it at all. Thrown off first by the sporadic dates and difficulty to organize the video tapes, then second by the startlingly large gap of time in the middle in which nothing relating to the narrative happens, many completely miss what is, at the core of it, the most vital part of the story.

Newcomers to the Aperture Record don't know how lucky they are. Dedicated teams of compilers, editors, archivers - anything you could hope for, all have spent the last 5 years tirelessly turning this thing inside out and pinning its delicate wings to the cardboard for us. For that we should be eternally grateful. As of this year, the original 25 and a half hours of security camera footage has been neatly spliced down by dedicated Aperture Record forum members to a 12 hour definitive cut, known among its few fans as the Chell Cut.(footnote) Twelve hours is still, of course, a formidable chunk of time - but unlike the 13 extraneous hours left out, the Chell Cut contains no downtime, empty shots, broken or otherwise uninterpretable cameras, and, most importantly: focuses on one central character all the way through.

Due to the impersonal distance of the cameras and sporadic lack of audio, it took years after the Record's discovery for anybody to notice the consistent reappearance of one specific figure. Earlier tapes in the footage reveal countless test subjects(footnote) and countless chambers as well, warming the viewer to the insinuation that each body is a new one, each room a unique configuration, each variable different. An insinuation so strong, in fact, that some individuals reject the Chell Cut entirely. As Rina Mai Bauchene argues: "It's just entirely unfeasible. Look at the evidence for and against this ridiculous connection: on the one hand, you've got a single document and a picture - on the other, you've got fuzzy, low-quality video cameras, a subject that never sits still let alone looks directly into the cameras, and a human mind that instinctually desires patterns and connections. It's a classic example of top-down processing, we're applying preconceived notions with the desire for a consistent and singular narrative."(footnote)

The issue with this, of course, is that we are already dealing with an exercise in impossibility. Adding the sums of unlikelihood together and subtracting it from believability does not a more coherent narrative make. For the sake of this publication, I would like to engage with every possibility - especially those that are popular within the online community surrounding the Record.

After all, this is a story about connection, despite it all. Who would we, as analysts be, without making connections?

There are, of course, inconsistencies and difficulties which must be addressed first and foremost. Bauchene is not incorrect in her steadfast insistence that the timeline doesn't line up. The time period in general is subject to debate and personal interpretation, and stubbornly refuses to be nailed down to a single decade, yet alone year.(footnote) Most frustrating of all, our saving grace, the security camera timestamps, become glitched and useless partway through the collection just as a visible jump in time happens within the tapes. Any speculation on how much time has passed is left as just that - speculation.

Despite all this, there are a nonzero amount of steadfast believers in the Record's authenticity, and while this analysis is meant neither to accept nor to reject the supposed "reality" of the work, it is worthwhile to mention them as well. Hyeon Francois-Weber's impeccably detail-oriented thesis The Aperture Timeline is a wonderful resource for those minute little bits of information that may otherwise be overlooked by less careful observers, and provides a handy visual diagram of each major event included within the Record - according to Francois-Weber's interpretation, of course. Michi Van Alst's "Fine, I'll Do What None of You Will." published within (insert journal here) is another publication heavily referenced within the creation of this analysis.

All that to say, whether you approach the Record as real or fake, it is far and away more important to approach with an open mind, and a willingness to look past inconsistencies and see a painting, rather than brushstrokes.

We begin in the depths of Aperture itself.

- A detailed list of each item contained within the Aperture Record can be found in Appendix A.

- Aperture's humble beginnings are only indirectly alluded to within the Record - small snippets of dialogue from various recordings and bits and pieces within the company files are all we have to go on to put together how exactly this seemingly massively influential company got started. Keen-eyed observers have managed to string together a handful of evidence from screenshots of security camera footage and allusions within the Cave Johnson pre-recorded messages5 that point towards small origins within shower curtain production. While we will be discussing them more in-depth, a quick look at this evidence can be found within the Chell Cut, at [insert timestamp here].

- Discussed more thoroughly in Chapter []

- Jo Chanda Ruiz, in their highly disruptive article "Finnegan's Lab: The Beginning and the End of The Aperture Record and Why Neither of Them Exist" first published in Shutter, Speed, Shutter v.12, October 31st, 1999 is first to name these two distinct parties. They also provide invaluable insight into the futility of classifying any one strategy as "correct" or "incorrect," noting the importance of approaching the Aperture Record from every angle in order to glean the most information.

- See Dagný Berne's "It Was You, All Along" in Mirrors and Ties, ed. Gustav Menelaos Foster (Michigan: Salt of the Earth Press, 1998)

- For a more focused look at our brave surrogate-explorer and hidden-within-the-narrative main character, see Chapter 3.

- Here lies one of many points of contention for Aperture skeptics. While the video quality is lacking, especially in older tapes, there are some distinct and very recognizable faces in the crowds of test subjects. Many consider this a tongue-in-cheek bit of post-production magic - one bit of audio from the Cave Johnson pre-recorded messages mentions the test subjects being "Astronauts, war heroes, Olympians…" and indeed, taking a closer look at the test subjects' faces from the 1950's era, anybody with some knowledge of history would recognize the visages of some of the most prominent astronauts and American Olympians of the time.(footnote) As of publication, every identified individual within the tapes has since passed, so asking them if they remember their time in the test chambers is, sadly, not possible. The debate rages on.

- LIST OF NOTABLE APERTURE TEST SUBJECTS: • Lindy Remigino • Andy Stanfield • Mal Whitfield • Harrison Dillard • Charles Moore • Horace Ashenfelter • Harrison Dillard • Lindy Remigino • Dean Smith • Andy Stanfield • Walt Davis • Bob Richards • Jerome Biffle • Parry O'Brien • Sim Iness • Cy Young • Bob Mathias • Mae Faggs • Catherine Hardy • Barbara Jones • Janet Moreau • Ron Bontemps • Marc Freiberger • Wayne Glasgow • Charlie Hoag • Bill Hougland • John Keller • Dean Kelley • Bob Kenney • Bob Kurland • Bill Lienhard • Clyde Lovellette • Frank McCabe • Dan Pippin • Howie Williams • Nathan Brooks • Charles Adkins • Floyd Patterson • Norvel Lee • Edward Sanders • Frank Havens • David Browning • Sammy Lee • Pat McCormick • Charlie Logg • Tom Price • Robert Detweiler • James Dunbar • William Fields Wayne Frye • Charles Manring • Richard Murphy Henry Proctor • Frank Shakespeare • Edward Stevens • Britton Chance • Edgar White • Sumner White • Everard Endt • John Morgan • Eric Ridder • Julian Roosevelt • Emelyn Whiton • Herman Whiton • Joe Benner • Clarke Scholes • Ford Konno • Yoshi Oyakawa • Ford Konno • Jimmy McLane • Wayne Moore • Bill Woolsey • Tommy Kono • Peter George • Norbert Schemansky • John Davis • William Smith • Thane Baker • Bob McMillen • Jack Davis • Gene Cole • Ollie Matson • Charles Moore • Mal Whitfield • Ken Wiesner • Don Laz • Meredith Gourdine • Darrow Hooper • Bill Miller • Milt Campbell • Miller Anderson • Paula Myers-Pope • John Price • John Reid • Ford Konno • Stanley Stanczyk • James Bradford • Jay Thomas Evans • Henry Wittenberg • James Gathers • Ollie Matson • Arthur Barnard • James Fuchs • James Dillion • Floyd Simmons • Bob Clotworthy • Zoe Olsen-Jensen • Juno Irwin • Charles Hough, Jr. • Walter Staley • John Wofford • Arthur McCashin • John Russell • William Steinkraus • Matt Leanderson • Carl Lovsted • Al Rossi • Al Ulbrickson • Richard Wahlstrom • Arthur Jackson • Jack Taylor • Evelyn Kawamoto • Jody Alderson • Josiah Henson • Loren Acton • James Adamson • Thomas Akers • Buzz Aldrin • Andrew Allen • Joseph Allen • Scott Altman • William Anders • Clayton Anderson • Michael Anderson • Dominic Antonelli • Jerome Apt • Lee Archambault • Neil Armstrong • Jeffrey Ashby • James Bagian • Ellen Baker • Michael Baker • Daniel Barry • John-David Bartoe • Charles A. Bassett, II • Alan Bean • Robert Behnken • John Blaha • Michael Bloomfield • Guion S. Bluford • Karol Bobko • Charles F. Bolden, Jr. • Frank Borman • Charles E. Brady, Jr. • Vance Brand • Daniel Brandenstein • Roy D. Bridges, Jr. • Curtis L. Brown, Jr. • David Brown • Mark Brown • James Buchli • Jay Clark Buckey • John S. Bull

- Bauchene, Rina Mai "In Response to The Aperture Forum and Their Inane Theories." Aperture Monthly, v.6, November 13th 2001, pp.2.

- The pastiche of American decade aesthetics that can be found throughout the Aperture Record is vastly intriguing, and subject to a handful of enlightening thinkpieces. Consider "How the Past Represents the Present: Y2K Obsession with Atompunk" by (insert name here) and "The Retro Renaissance in the Record" by (insert name here), in which (author) makes the startling, yet sound, theory that the fixation with atompunk retrofuturist aesthetic is actually a reflection of early-aughts sentiment, rather than the 60s-70s-80s time period it's intending to evoke.